Slowly the temperature climbed and Michael and Denis kept peering in to the Kiln waiting for the magical temperature of 1300 degrees C. This was the key heat that would turn the clay to stone and melt the glazes sufficiently.

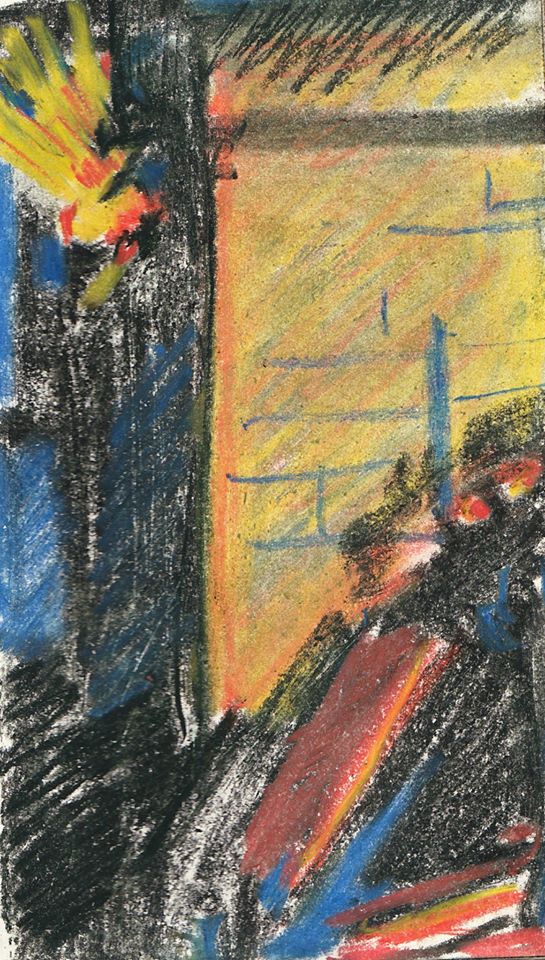

Time dragged on into the afternoon and into early evening. We continued to keep the barrels fed as it dripped and sprayed. As the light faded the magic grew, the light from the fire box sending out a warm glow which fell over our worn, tired, blackened miner-like faces and silhouetted theblack trees closing in around us. Finally, the two judged, with nodding heads that it was time to do the reduction:

Quote from Ceramic Review Article Nov – Dec 1974 issue no 30

“Firing conditions:

We fire the kiln with wood to 400 degrees and thereafter with oil to 1300 degrees. We have found that the steady reduction from 900 – 1300C by slightly over fuelling, produces the best colours. We maintain a smokey flame at the spy hole with a light grey plume of smoke issuing from the chimney. We usually soak for 1/2 to 3/4 of an hour. Further reduction can be obtained on cooling say to 1100C holding this and smothering the kiln again for about 1/2 hour.”

For all its calm simplicity, this quote, was somewhat misleading as reduction meant reducing the amount of oxygen to feed the fire and this of course could mean reduction in the temperature. The idea was to reduce for a short time, starving the fire of oxygen and force the fire to draw oxygen from the oxides in the glazes, but to do this without reducing the oxygen by too much, delicate operation. This was discovered by the Chinese potters some thousands of years ago and by this means they managed to create high fired stoneware pieces with wonderful vivid and rich colours that would never change, fade or deteriorate.

This chemistry, which I later read about with the help of Michael and a very old school chemistry book by Holmyard gave me an insight into the mystery of glazes and firing, which I had know idea of at the time.

To be continued: